Mutual Fund Valuation

Every trading day, the assets of a mutual fund are “marked to market”, meaning the values of all securities held by the fund are determined using the latest closing prices. The total value of the fund is divided by the total shares outstanding, rendering a net asset value (NAV) per share. For no-load mutual funds, this NAV is the price used to buy and sell shares. As the NAV represents the actual worth of a fund, it is the only fair price one should consider paying or receiving for shares.Front-End Loads – ‘A’ Shares

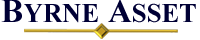

The oldest and most common mutual fund sales charge is the front-end load. Also termed class ‘A’ shares, these funds strip away some of your money right at the start. In addition to paying the NAV for your fair share of fund assets, you pay a commission. For instance, if you invest $100,000 into funds with a 5% load, on day one, before any market movement, your assets will be down $5,000. Only $95,000 will be invested. $5,000 will go to salespeople.

Back-End Loads Part 1 – ‘B’ Shares

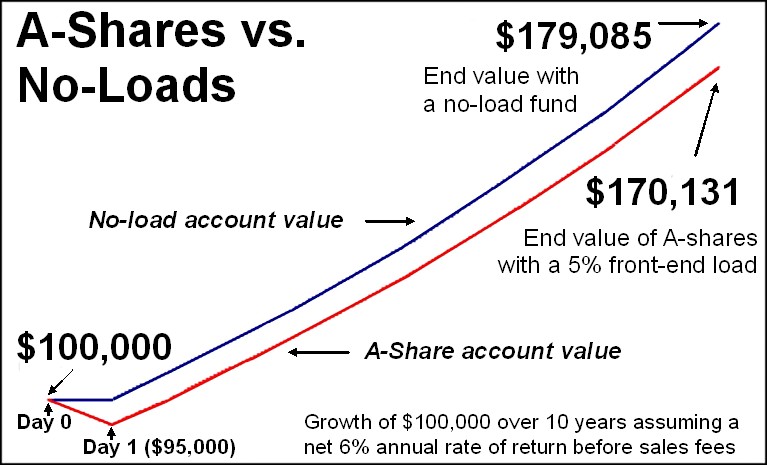

Back-end loads, sales charges that hit when money is withdrawn, were introduced chiefly to assuage the ill will that was often incited when prospects learned of the front-end loads. Back-end loads allow a salesperson to assure you that a $100,000 investment will render a $100,000 account balance on day one. Unfortunately, commissions are still going to be taken out of your portfolio. First, ‘B’ shares entail extra annual charges. In addition to normal management and administrative expenses, ‘B’ shares tack on distribution charges that often range between .75% and 1%. Usually identified as 12b-1 fees, these charges deplete assets over a period of 5 or more years – basically until the equivalent of the “avoided” front-end load has been sucked out. Second, there are back-end penalties. To make sure sales reps can get their full commission, ‘B’ shares stipulate a series of penalties that hit if you sell such shares within the first few years of ownership. For example, a fund might have a 5% penalty in effect the first year, a 4% fee effective the second year and so on until the penalty disappears in the sixth year. Of course, during this entire period the aforementioned extra annual charge would be in effect. Taking into account both the annual and back-end fees, you are contractually hit with a full sales charge upon purchase of either ‘A’ or ‘B’ share mutual funds.

Back-End Loads, Part 2 – ‘C’ Shares

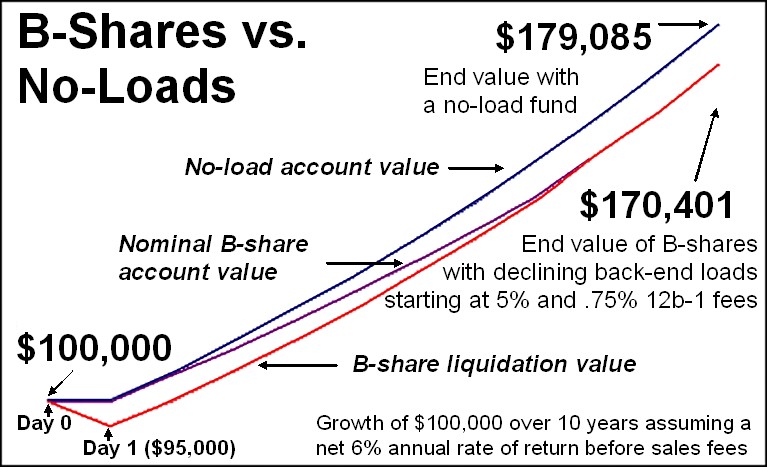

In a normal investment cycle, people will want to change holdings or even pull out money. The punitive nature of ‘B’ share mutual funds not only causes material harm upon withdrawal but also fosters a reticence to shift assets even when prudence or need dictate such a withdrawal. To provide commissions and yet allow for more flexibility, the class ‘C’ share was created. As with ‘B’ shares, ‘C’ shares allow a salesperson to state that $100,000 invested will provide an account balance of $100,000 on day one. While ‘C’ shares have a back-end penalty, it is usually far less than that of ‘B’ shares. A fund whose class ‘B’ shares present a 5% back-end penalty might be matched with a class ‘C’ share with a liquidation penalty of 1%. Further, similar to ‘B’ shares, ‘C’ shares also add on annual 12b-1 fees, usually in the .75% to 1% range. The main catch with ‘C’ shares is that the fees are never dropped. The annual distribution fee constantly siphons your assets and no matter how many years pass you will be hit with a penalty upon withdrawal. Though superficially cheaper and more flexible than the other loaded share classes, in the long run ‘C’ shares are the most damaging.

Misleading Sales Talk

Salespeople are taught various phrases and presentation techniques to make you feel like skimming your money is standard practice and immaterial. Often prospects are shown charts showing long term growth. Impressive as those charts appear, they mask the far greater growth that would have occurred without the sales charges. Occasionally you may hear stories about a fund’s unique nature, and that to invest in such a great vehicle one is required to pay a sales fee. This is a fallacy. For every sales fee loaded mutual fund, there are many no-load options with equivalent exposure and equal, perhaps even superior, management. Lastly, a salesperson, using the title advisor or consultant, might tell you that the extra fees represent compensation for his or her expertise. This is an abject lie. Management fees pay for portfolio managers who invest fund assets. Loads, 12b-1 fees, and back-end penalties are sales charges – plain, simple, and avoidable.What to do?

To save substantial money and thereby increase expected returns, it is wise to do a quick check of all mutual funds owned directly and within company run retirement plans. Sites such as Google Finance and Morningstar allow you to look up ticker symbols and check for the existence of front loads, back loads, and 12b-1 expenses. Shares in any funds that have any of these fees should be sold. To maintain the same market exposure, use a screen such as that found at Morningstar to include only no-load funds with similar underlying investments and double check for 12b-1 charges. Additionally, if your firm’s 401k plan is dominated by ‘B’ and ‘C’ share funds, talk to your administrator about switching to another platform. If your 401k assets are with a former employer, transfer those assets into an IRA, preferably at a low cost broker or a no-load mutual fund platform.This article was originally published in NJ Esq August 8, 2008.